WALKER, Mich. — When firefighter Jared Yax's pager goes off, he faces the usual split-second decision: drop what he's doing, race to the Walker Fire Department station, and respond to an emergency. But Yax brings something unique to the fire truck — specialized training in protecting art and cultural artifacts from disaster.

Yax is one of fewer than 200 people nationwide certified as a National Heritage Responder through HEART (Heritage Emergency and Response Training), a program sponsored by the Smithsonian Institution and FEMA that prepares emergency responders to protect cultural heritage during disasters.

"I help museums or cultural institutions find resources that they need in an emergency, or to be able to train them to prepare for an emergency," said Yax, who spells his last name Y-A-X.

For Yax, firefighting represents a secondary career built on family tradition. His grandfather and great-grandfather were both paid-on-call volunteer firefighters in the Bay City area's Bangor Township.

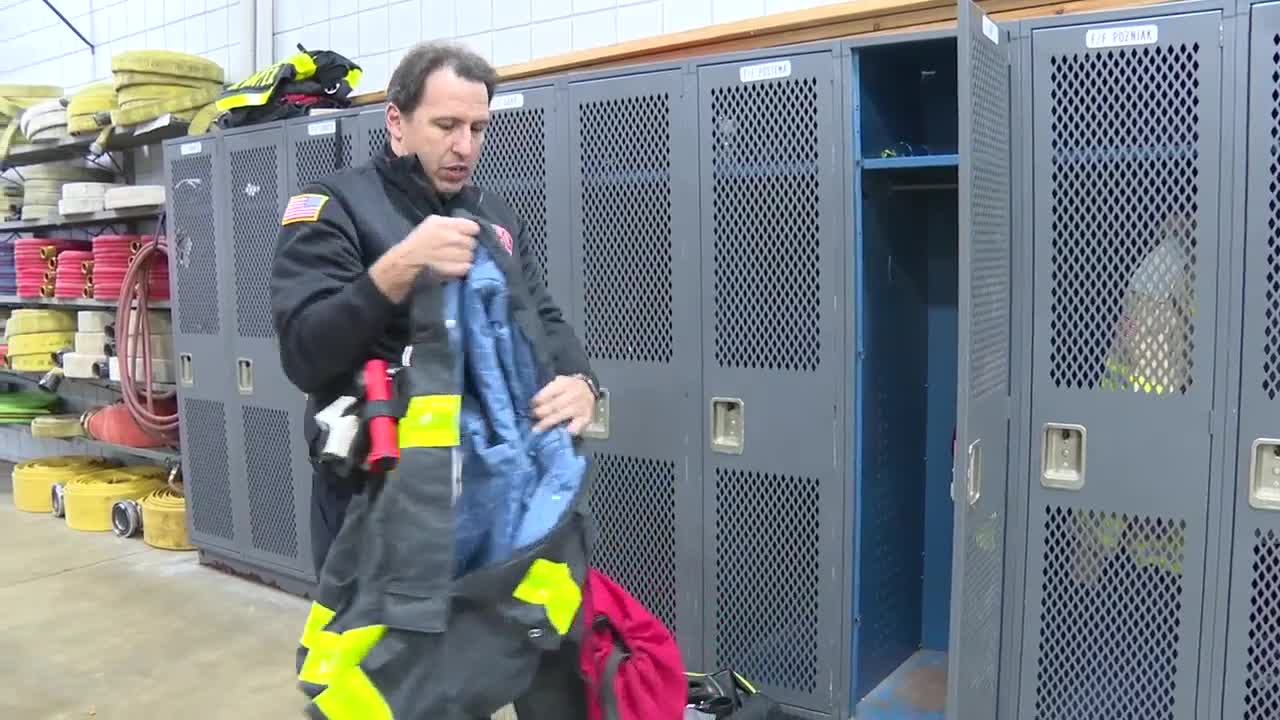

"When my pager goes off, I jump in the car, run to the station, grab my gear, jump on the engine, and we go to the emergency," he explained.

But his primary career for more than 20 years has been as a museum curator. A Grand Valley State University graduate with degrees in history, archaeology and German, Yax is currently developing a consulting practice as a Heritage Emergency Responder.

When disasters strike cultural institutions, Yax applies training that's vastly different from typical emergency response protocols.

"Museums and cultural institutions are a very unique type of institution to try and help out in a disaster," he said. "We almost have to treat it like a mass casualty incident. But instead of people as patients, you've got all these artifacts."

Each artifact requires individual condition reports, triage forms and conservation plans. Museums housing hundreds of thousands or millions of objects create extremely complex rescue operations.

"One of the things that I specialize in is the Incident Command System for heritage sites," Yax said. "It's a command and control system that helps you manage time, people and resources in an emergency. A lot of museums aren't used to the thought of using a plan like that that fire departments or FEMA use all the time."

Yax's specialized knowledge becomes crucial for protecting both artifacts and firefighters, as historic materials can contain unexpected hazards.

"When you're looking at objects from the Victorian era, fabric that was dyed green, they used arsenic to dye it," he explained. "So if that's on fire, all of a sudden, that's being aerosolized and could potentially affect the people that are trying to mitigate the disaster."

This represents just one of countless potential hazards hidden within museum collections — knowledge that can prevent serious health risks for emergency responders.

Heritage emergency response involves working under extreme time pressure to prevent permanent damage.

"A lot of times you only have days or hours before mold or mildew will set in and start to permanently damage an object," Yax said. "You have to worry about the carcinogens from the smoke from a fire affecting the artifacts."

The work continues long after fires are extinguished, as teams assess structural damage and determine whether artifacts need immediate evacuation from unstable buildings.

In September, Yax deployed to Brooklyn, New York, to assist with a massive five-alarm warehouse fire in the Red Hook area that destroyed hundreds of artist studios.

"The New York Fire Department fought that fire for quite a while," he said. "At one point, I think one of the articles said they were dumping 50,000 gallons a minute on it to put that fire out."

The disaster affected thousands of pieces of artwork with fire, water, soot, smoke and ash damage. Yax helped establish the Incident Command System to organize rescue efforts, coordinating with approximately 400 volunteers who assisted in recovery operations.

"I was deployed to help them put together that ICS system to help them organize their rescue efforts, so that way they're able to manage the time, people and resources they need to evacuate that art out of the fire-affected space and into a triage space where we could try to stabilize it," he said.

Yax describes his hands-on role as similar to emergency medical care for cultural objects.

"I do stabilization treatment, preservation treatment. I am not a conservator — that's completely different schooling," he said. "I'm kind of what you would consider like a paramedic for the artifacts, whereas the conservator is going to be a surgeon."

His job involves stabilizing artifacts and stopping ongoing damage, preparing them for professional conservators who perform restoration work.

Within Walker city limits, Yax's expertise applies to numerous institutions that residents might not consider cultural heritage sites.

"Churches are considered cultural institutions, any place that's displaying art is like a little art show or art gallery," he said. "It's not just history museums. It's any type of cultural institution. The library would be considered a cultural institution."

He also assists private citizens with questions about protecting family heirlooms and artwork, providing advice on disaster preparation and post-emergency care.

Yax belongs to the National Heritage Responders, a nonprofit group of about 100 specialists who provide emergency consultation through a hotline system.

"They've got a hotline that institutions can call and get advice from curators across the country," he said. "Paper conservators, art conservators, people that specialize in emergency response like myself can give them advice within hours or days of an event."

He now serves as an instructor for the Smithsonian's HEART program, traveling to Washington, D.C., each December to teach new participants.

"The knowledge that I've gained through the Walker Fire Department, I use in teaching at the Smithsonian there, so our city here is influencing Cultural Heritage Emergency Response on a national level," Yax said.

Heritage emergency response represents a relatively new specialty combining emergency management with cultural preservation.

"It's a relatively new part of both the emergency management field and the museum field," Yax noted. "The program at the Smithsonian, the HEART program, has only been around for maybe about six or seven years."

The HEART program accepts about 25 participants annually from a competitive applicant pool representing cultural heritage institutions and first responder organizations across the United States.

The work of National Heritage Responders like Yax relies entirely on donations, as these specialized services aren't typically covered by traditional emergency funding sources.

The nonprofit organization maintains its hotline service and deployment capabilities through public support, ensuring that communities across the country can access this crucial expertise when cultural disasters strike.

Here's their GoFundMe.

This story was initially reported by a journalist and has been converted to this platform with the assistance of AI. Our editorial team verifies all reporting on all platforms for fairness and accuracy.